Nepal Leader Revives Chinese Dam Project

Nepal’s new communist prime minister will restart a Chinese-led US$2.5 billion hydropower project that was pulled by the previous government considered friendly towards India, and wants to increase infrastructure connectivity with Beijing to ease the country’s reliance on New Delhi.

He also wants to “update” relations with India “in keeping with the times” and favours a review of all special provisions of Indo-Nepal relations, including the long-established practice of Nepalese soldiers serving India’s armed forces.

“Political prejudice or pressure from rival companies may have been instrumental in scrapping of the project. But for us, hydropower is a main focus and come what may, we will revive the Budhi Gandaki project,” Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist-Leninist) leader Khadga Prasad Sharma Oli told the This Week in Asia in an exclusive interview, his first since taking office on Thursday.

The contract to build a dam on the Budhi Gandaki river in central-western Nepal turned into a political hot potato after it was awarded last June to China’s Gezhouba Group by a government headed by Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Centre) leader Pushpa Kamal Dahal, as part of China’s “Belt and Road Initiative” that Nepal joined the previous month. The next prime minister, from the Nepali Congress, scrapped the project, in a move seen as a concession to pressure from India, which has been wary of a growing Chinese footprint in what it sees as its sphere of influence.

Oli’s UML and the Maoist Centre formed the Left alliance that swept to power in this landmark election, Nepal’s first after the promulgation of its new constitution restructuring the Himalayan country as a federal republic. The two communist parties are also inching towards a merger, which China has always advocated.

“Our petroleum usage has been increasing but we import all of it. We urgently need to develop hydropower to reduce our dependence on petroleum,” Oli said.

Almost all of Nepal’s petroleum is imported from India. Its fuel import bill has tripled in the past five years, adding to the ballooning trade deficit with India, which stood at around US$6 billion in the last financial year (July 15, 2016 to July 15, 2017). The trade deficit with India constitutes about 80 per cent of Nepal’s overall deficit.

Nepal’s emphasis on hydropower has made it an arena of shadow boxing between the two regional giants. India’s GMR and SJVN have been given the contracts for two other dam projects while China’s Three Gorges Corporation is to develop another.

Oli’s rift with New Delhi, which it had blamed for engineering his government’s fall in August 2016, has been growing in recent years. As prime minister between 2015 and 2016, he locked horns with India over Nepal’s new constitution, which New Delhi resisted on the ground that it discriminated against people of the southern plains of Nepal adjoining India who are of Indian ancestry.

Krishna Bahadur Mahara, Nepal’s deputy prime minister, meets with Premier Li Keqiang in September. Photo: Reuters

When India retaliated with a crippling blockade of the landlocked country, he reached out to China to overcome the crisis and inked several vital agreements. He later cancelled a visit by Nepal’s president to India and recalled the Nepalese ambassador to the country, in rare acts of defiance by a Nepalese leader against the dominant southern neighbour. In this election, Oli successfully tapped the groundswell of anti-India sentiment in Nepal as a result of the blockade, lacing his stump speeches with rhetoric against India that fetched his party 121 seats in the 275-member Parliament.

But back in power, he is weighing his words more carefully.

“We’ve always had excellent relations with India. There were some elements in the Indian establishment that caused some misunderstanding, but Indian leaders have assured us that there will be no interference in the future and we will respect each other’s sovereign rights,” he said.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, too, has been trying to mend fences. He has called Oli three times since he won, and sent External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj this month to reinforce the message of cooperation. Delhi is particularly concerned about growing Chinese interests in Nepal, the latest South Asian country that appears to be drifting away from India’s control. Maldives is now run by a man who makes no bones about courting China and playing it off against India, while massive Chinese investments have deeply entrenched Chinese interests in Sri Lanka.

Indian External Affairs minister Sushma Swaraj was dispatched to Kathmandu to try to mend fences this month. Photo: AP

But despite the careful diplomatese of peace and goodwill with India, Oli is keen to broaden his options by deepening ties with China to get more leverage in his dealings with Delhi. “We have great connectivity with India and an open border. All that’s fine and we’ll increase connectivity even further, but we can’t forget that we have two neighbours,” Oli said. “We don’t want to depend on one country or have one option.”

He sees infrastructure development as an important means to narrow the distance with China, whose physical remoteness compared with next-door India is a hindrance to deeper Sino-Nepal relations.

“Technology allows us to reimagine distance. Can you believe that in 1970, it used to take me two days to reach Kathmandu from my home in eastern Nepal?

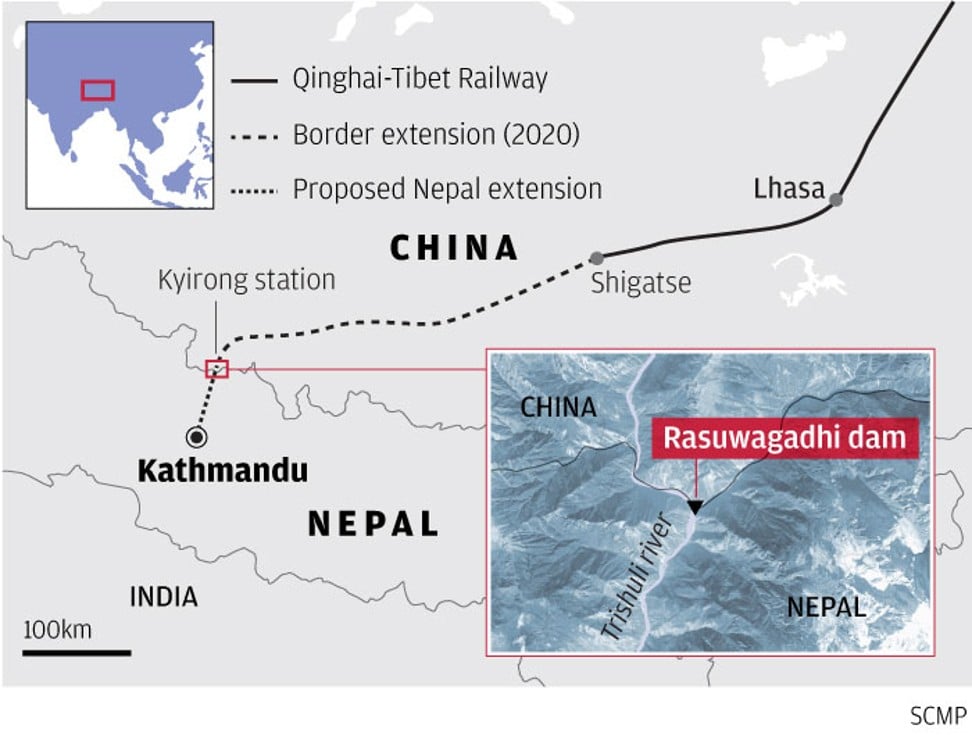

“Once China brings its rail network up to Shigatse and then Kyirong in Tibet, it should be easy to extend it to Nepal. It’s lower altitude than Tibet, and the terrain is actually sloping all the way down from Kyirong. Apart from that, three roads are under construction connecting China and Nepal, which should be ready in a couple of years. If we can connect this railway network to our east-west rail project, it can revolutionise China-India trade, with Nepal in the middle” he said.

Nepal’s government hopes the dam, seen here in an illustration, will help lower fuel costs. Photo: Handout

China aims to extend the Qinghai-Tibet railway to the Nepal border by 2020 and has expressed interest in extending it to Kathmandu. Kyirong in Tibet is about 25km from Nepal’s Rasuwagadhi border transit point, which is 50km from Kathmandu. The Nepalese government is understood to be working on a plan to build a road tunnel between Rasuwagadhi and Kathmandu that will radically shorten the travel time.

Apart from infrastructure and power, cyber connectivity is also among Oli’s thrust areas. Nepal last month ended India’s monopoly in the field by joining forces with China to offer internet services to its people after laying optical fibre cables between Kyirong and Rasuwagadhi.

The loss of a captive internet market is a sign of the increasing competition India is facing in the country it once dominated as China makes deep inroads. The Indo-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship of 1950, which Nepalese nationalists believe compromises Nepal’s ability to pursue an independent defence and foreign policy, is also being revised. But despite their recent differences, India and Nepal share deep historical and cultural bonds, apart from an open border that allows millions to freely work and travel in each other’s territory. More than 25,000 Nepalese serve in the Indian Army and another 20,000 Nepalese are in Indian paramilitary and police forces, an arrangement that offends some in Nepal.

“This should be internally and mutually discussed and corrected, if necessary. We live in a new world, and Nepal is starting a new journey, we have to update whatever is considered outdated and bring it in line with the modern era,” Oli said.